More education in the health care setting and among women could help close the disparity in how women, men fare with heart and vascular disease.

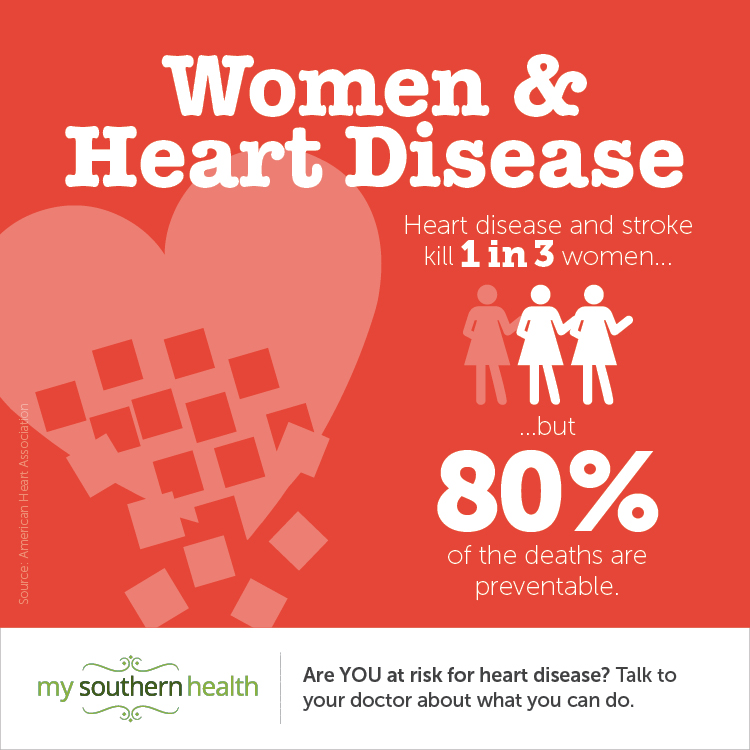

Heart and vascular disease remains the leading cause of death for women worldwide, including in the United States. Risk increases with age and with other risk factors (including family history, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking and obesity).

Multiple nationwide initiatives have been implemented in recent decades to increase awareness of the significance of these risks and of heart disease in women. These have been associated with a decrease in rates of death from heart and vascular disease, but a gap between how women and men fare remains.

For years we have known that there are disparities in diagnosis, treatment and outcomes for women and men with heart disease. A recent study showed that in young patients with heart attacks, women had less frequently been told that they were at increased risk or been counseled on ways to reduce this risk. When describing symptoms that could be due to heart artery blockages, women are less likely to be referred for diagnostic testing.

In addition, when having a heart attack, women less frequently receive the most aggressive treatments compared to men. This includes both aggressive medical therapy and procedures to open blocked arteries. The treatment that women do receive in this setting is more likely to be delayed compared to men. Rates of death in women after a heart attack are higher; this has recently been shown to continue to be true even in younger women. For women with heart disease, the likelihood that they will achieve goals in risk factors reduction, such as ideal diabetes and cholesterol control, is lower.

Reasons for gap are varied

Some of this gap can likely be attributed to biological differences in men and women. For example, women are at different risk than men due to hormonal influences that vary during their lifetimes. There may be differences in the extent and the degree of heart artery blockages in men and women with heart artery disease. Some of the well-known risk factors for heart disease occur in different rates in women and men. In some circumstances, women may respond differently to medications than men, which can impact the effective treatment of heart disease.

Other contributing factors are not biological.

Among the general population as well as in the health care setting, a woman may be perceived to be at lower risk for heart disease than a similar male patient. A woman will more frequently present with symptoms other than chest pain, such as shortness of breath, nausea, or pain in the arms or jaw.

Both of these factors may decrease the likelihood that she will seek timely evaluation and that her symptoms will be recognized. Women have historically been underrepresented in studies relied on to determine the best care for patients with heart disease, making it more difficult to know if this information applies equally for both genders.

What can be done to address these disparities? We have made progress, but work remains to be done.

From a health care system perspective, there needs to be continued emphasis on increasing health-care provider awareness about heart and vascular risks for women and a focus on more aggressive diagnosis and treatment. The incidence of inclusion of women in clinical studies has been on the rise, and this will help ensure that we know the best gender specific treatments.

Individually, women need continued education about heart disease and how to lower the risk, starting at a young age. Within our homes and communities, we have tremendous power to emphasize healthy lifestyle choices, thereby providing encouragement to other women around us.

Knowing the disparities that still exist, women should also feel empowered to advocate for evaluation and treatment for themselves, friends and family members. Working together, as individuals and in our health-care system, we can continue to improve the outlook for women with heart and vascular disease.

Julie Damp, M.D., FACC, was raised in Shelbyville, Tennessee, and earned her undergraduate degree in Biomedical Engineering from the University of Tennessee. She graduated from Vanderbilt School of Medicine in 2001 and completed her internal medicine and cardiology fellowship training at Vanderbilt in 2007. She is Associate Professor of Medicine and Associate Director of the Cardiovascular Fellowship Training Program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Read more about heart attack symptoms in women from the American Heart Association.

The Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute‘s team treats all types of cardiovascular diseases and conditions, from the common to the complex. Our team is consistently recognized by U.S. News & World Report among the best heart hospitals in the nation and the best in Tennessee. Our wide range of services are offered in convenient locations throughout the region.